Lots of entrepreneurs struggle with pricing. How much to charge? It’s clear that the right price can make all the difference—too low and you miss out on profit; too high and you miss out on sales.

Don’t ask, can’t tell: Asking people what they’d pay for and how much rarely works. [Tweet it!]

For one thing, people will tell you what they want to pay—which is obviously much less than what your product or service is actually worth. Second, what people say they would do and what people end up doing are very different things.

When it comes to money, people are unable to predict accurately whether they’d pay or not. It’s much easier to spend hypothetical dollars than real ones.

Also, it’s worth remembering that people really don’t know how much things are worth or what’s a fair price (which is the reason TV shows like “The Price Is Right” can actually exist).

William Poundstone, the author Priceless: The Myth of Fair Value, says:

People tend to be clueless about prices. Contrary to economic theory, we don’t really decide between A and B by consulting our invisible price tags and purchasing the one that yields the higher utility. We make do with guesstimates and a vague recollection of what things are “supposed to” cost.

People are weird and irrational, and there’s much we don’t understand. For example, why do shoppers moving in a counterclockwise direction spend on average $2.00 more at the supermarket?

Why does removing dollar signs from prices (24 instead of $24) increase sales?

What will work for you depends on your industry, product, and customer. When you try to replicate what Valve did to increase their revenue 40x, it might not work for you, but then again, why not give it a try?

Here’s a list of pricing experiments and studies you can get ideas from and test on your own business.

Note: CXL Institute has original research on SaaS pricing pages. Find out how you should order your pricing plans to generate the most revenue, and what happens when you highlight a “recommended” plan.

Table of contents

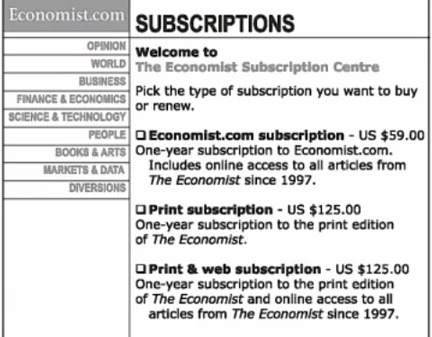

The Economist and decoy pricing

Dan Ariely describes this famous example in his amazing book Predictably Irrational. He came across the following subscription offer from The Economist, the magazine (he’s also explaining this in his TED talk):

Both the print subscription and print & web subscription cost the same, $125 dollars. Ariely conducted a study with his 100 bright MIT students. In it, 16 chose option A and 84 chose option C. Nobody chose the middle option.

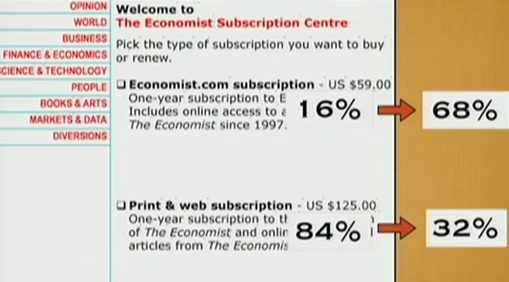

So if nobody chose the middle option, why have it? He removed it, and gave the subscription offer to another 100 MIT students. This is what they chose now:

Most people now chose the first option! So the middle option wasn’t useless, but rather helped people make a choice. People have trouble comparing different options, but if two of the options given are similar (e.g., same price), it becomes much easier.

The same principle was used with travel packages.

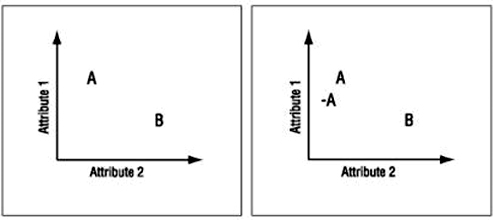

When people were offered to choose a trip to Paris (option A) versus a trip to Rome (option B), they had a hard time choosing. Both places were great—it was hard to compare them.

Now they were offered three choices instead of two: trip to Paris with free breakfast (option A), trip to Paris without breakfast (option A-), trip to Rome with free breakfast (option B). Now overwhelming majority chose option A, trip to Paris with free breakfast. The rationale is that it is easier to compare the two options for Paris than it is to compare Paris and Rome.

A graph to describe this:

So if you add a slightly worse option that is similar to A (call it A-), then it’s easy to see that A is better than A-, which is why many people choose that.

How you can use it: Add a decoy package or plan to your offer page next to the offer you really want them to take.

The magic of number 9

Go to Walmart and you’ll see prices ending with 9 everywhere. Does it really work? Surely all intelligent people understand that $39 and $40 are basically the same.

Well, in eight studies published from 1987 to 2004, charm prices ($49, $79, $1.49, and so on) were reported to boost sales by an average of 24% relative to nearby prices (as per Priceless).

In one of the experiments done by University of Chicago and MIT, a mail order catalog was printed in three different versions. One women’s clothing item tested was sold for $39. In experimental versions of the catalog, the company offered the same item for $34 and $44. Each catalog was sent to an identically sized sample.

There were more sales at the charm price of $39 than at either of the other prices, including the cheaper $34. The $39 price tag had both greater sales volume and greater profit per sale.

People used to download music for free, then Steve Jobs convinced them to pay. How? By charging 99 cents.

The explanation of why numbers ending with 9 work better has been much debated over the years. Mental rounding alone can’t explain it. Seems that 9 truly is a magic number.

Is there anything that can outsell 9?

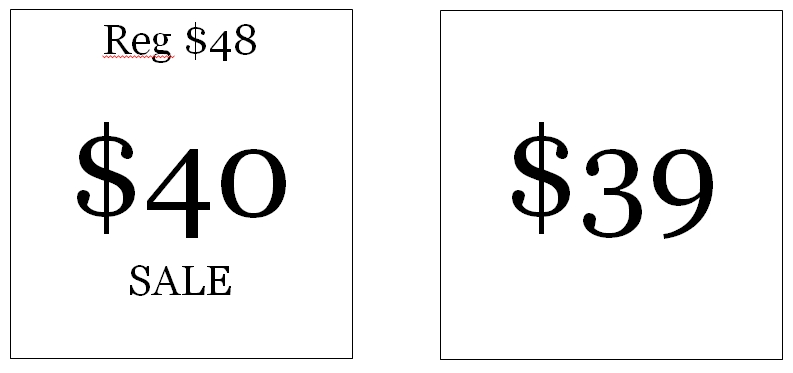

Researches found that sale price markers (with the old price mentioned) were more powerful than mere prices ending with the number 9. In the following split test, the left one won:

Number 9 not so magical after all? Not so fast!

Then they split-tested the winner above with a similar tag, but which had $39 instead of $40:

This had the strongest effect of all.

I’m wondering whether the effect of this price tag could be increased by reducing the font size of $39. Say what?

Marketing professors at Clark University and The University of Connecticut found that consumers perceive sale prices to be a better value when the price is written in a small font rather than a large, bold typeface. In our minds, physical magnitude is related to numerical magnitude.

Oh yeah, when you go to Nordstrom, you don’t see any prices ending with a 9. The subliminal message here is “expect to pay.”

Anchoring and the contrast principle

Do this test at home. Pour water in three bowls. Fill one bowl with cold water, the second with hot water, and third one with lukewarm water. Now stick one hand in the cold water and the other one in the (not too) hot water. Keep them there for 30 seconds or so. Now put both of your hands into the lukewarm bowl. One hand will feel the water is warm, the other one that it’s cold.

It’s about the contrast. The same principle applies to price. Nothing is cheap or expensive by itself, but compared to something.

Once you’ve seen a $150 burger on the menu, $50 sounds reasonable for a steak. At Ralph Lauren, that $16,995 bag makes a $98 T-shirt look cheap.

What’s the best way to sell a $2,000 wristwatch? Right next to a $12,000 watch.

This mental process has a name. It’s called anchoring and adjustment.

Anchoring

In the 1970s, two psychologists by the names of Tversky and Kahneman theorized that suggesting an initial figure to a test subject caused that subject to use that number as a starting point for estimating unknown quantities.

In their study test, subjects were told the number 65 and then asked to estimate what percentage of African nations were members of the UN. The average response was 45%. They then tested a second group but salted them with the number 10; their average response was 25%. Amazingly, the group that was primed with the number 65 estimated nearly twice the true answer (23%) while the group primed with the lower number estimated a lower percentage (much more accurately).

Anchoring influences prices

Poundstone describes an experiment done with real estate prices. The researchers invited real estate experts and undergrad students to appraise a home for sale. All the test subjects were given the information a buyer would normally have, including a list of houses that recently sold, nearby houses currently for sale and so on, as well as what the seller had listed the house for.

The subjects were divided into four groups, each given a different listing price, and were then asked to estimate what the home was worth.

These were the results:

| Listing Price | Avg Estimated Worth by Students | Avg Estimated Worth by Experts |

|---|---|---|

| $119,900 | $107,916 | $111,454 |

| $129,900 | $120,457 | $123,209 |

| $139,900 | $123,785 | $124,653 |

| $149,900 | $138,885 | $127,318 |

Anchoring worked even on real estate pros that had been selling properties in the area for 10+ years. Next time somebody asks you for a rough estimate or a ballpark figure, make sure it’s high!

How you can use it: Start throwing out high numbers. Add some very expensive products to the selection (that you don’t even intend to sell). If the final price of your product (or service) is a result of negotiations, start high. If you’re competing on price, state how much others are charging before revealing your price.

Straightforward pricing

Ash Maurya, a startup entrepreneur, published an article on VentureHacks describing his pricing experiments with a photo sharing service.

He tested a single, straightforward $49/yr offer versus two plans ($49/yr and $24/yr) versus three plans (adding a freemium plan).

The result? Surprisingly, the single price offer won. Why? His own guess:

It does pay to align pricing with your overall positioning. Our unique value proposition is built around being “hassle-free and simple,” and people seemed to expect that in the pricing model as well.

It might also be that in these complex and fast times we live in, people yearn for simplicity.

Note: His freemium plan actually converted 12% more, but had the lowest retention. Be careful when offering free plans. You might just end up with a ton of free users to support and pay for.

How you can use it: Consider your positioning and see if you can align your pricing to it. If you’re offering different plans right now, experiment with a single plan.

Pay what you wish

Pay what you want is a pricing system where buyers pay any desired amount for a given product, or nothing at all. In some cases, a minimum is set, and/or a suggested price may be indicated as guidance for the buyer. The buyer can also select an amount higher than the standard price.

Suggested price

Suggested price can be a good idea—remember anchoring? Setting a fair suggested price gives the customer a true sense of value. It won’t prevent low offers, but it will keep more buyers in your ballpark.

What about counter-offering lowballs? The danger here would be to appear that you’re just toying with them and it’s not really “pay what you wish.” GetElastic brings this example:

Coming back with counter-offers is merely e-bargaining. It reveals you have a reserve price, and instead of offering a sale, customers must “guess” how low you’ll go. At worst, customers may feel they are being gamed into pay more than a sale price.

Ashampoo Software (that’s not a typo) gets downright insulting when you sink too low below “regular price.” The snarky dialog box reads a condescending “This offer is much too low. Please enter a reasonable price.” Users don’t have time to play guessing games about what is a reasonable offer only to be ridiculed by a script.

Gap tried a variation of this too. They offered customers a one-day opportunity to name their price for certain styles of khaki pants on the www.gapmyprice.com microsite. Lowball offers were returned with slightly higher prices by the Gap, which the customer had one chance to accept or decline.

Since they’re not doing anymore, it probably did not go too well.

Well-known PWYW examples

In October 2007, the British band Radiohead launched their latest album, In Rainbows, on the Internet. The band allowed fans to download the album freely and offer, in retribution, any amount of money they would like. Later they disclosed that the download of their new album generated more profit than the accumulated downloads from all previous albums.

Panera Bread Co. used this same idea when it opened its first pay-what-you-want restaurant in Clayton, MO. The company ended up making over $100,000 in revenue in the first month alone. It opened its 4th restaurant of this kind in Portland, and said at the time that about 20% of the visitors to the cafes leave more than the suggested amount, 20% leave less, and 60% pay what is suggested.

But nine months later, it’s not doing so well. The Portland café is only making about 60% of the revenue of a regular, full-paying location, compared to an 80% take in the politer climes of St. Louis and Detroit. Also, the homeless tend to camp out there and stay all day if they aren’t shooed away, so Panera had to hire a bouncer.

It’s important to have fair minded customers for this model to work (homeless and hungry people probably care more about being fed than being fair).

Combine “pay what you wish” with charity

There’s some research that pay what you wish pricing works best when combined with charity. Ayelet Gneezy, a marketing professor at the University of California-San Diego, conducted a field experiment at a theme park (sample size: over 113,000).

Customers were presented four different pricing schemes for souvenir photos: a flat fee of $12.95; a flat fee of $12.95 with half going to charity; pay-what-you-wish; and pay-what-you-wish with half going to charity.

At a flat fee of $12.95 per picture, only 0.5% of people purchased a photograph; when customers were told that half the $12.95 purchase price would go to charity, a meager 0.59% purchased a photo. Under the simple pay-what-you-wish variation, 8.39% of people purchased a photo (almost 17 times more than before), but customers paid only $0.92 on average.

The final option—pay what you wish, with half the purchase price going to charity—generated big results: purchase rates of 4.49% and an average purchase price of $5.33, resulting in significant profits for the theme park. This is a substantial result, especially since it came from a real setting.

Of course, the anonymity of the Internet removes the social pressure one feels after being served personally by a human being. It’s one thing to have the amount you choose observed, and another thing to download stuff without being seen.

The book Smart Pricing suggested that successful pay what you want programs are characterized by:

- A product with low marginal cost;

- A fair-minded customer;

- A product that can be sold credibly at a wide range of prices;

- A strong relationship between buyer and seller;

- A very competitive marketplace.

Offering three options

The old truth about offering three pricing options holds water. Here’s a pricing experiment in selling beer, again from W. Poundstone’s amazing book Priceless.

People were offered two kinds of beer: premium beer for $2.50, and bargain beer for $1.80. Around 80% chose the more expensive beer.

Now a third beer was introduced, a super bargain beer for $1.60 in addition to the previous two. Now 80% bought the $1.80 beer, and the rest $2.50 beer. Nobody bought the cheapest option.

Third time around, they removed the $1.60 beer and replaced with a super premium $3.40 beer. Most people chose the $2.50 beer, a small number $1.80 beer and around 10% opted for the most expensive $3.40 beer. Some people will always buy the most expensive option, no matter the price.

You can influence people’s choice by offering different options. Old school sales people also say that offering different price point options will make people choose between your plans, instead of choosing whether to buy your product or not.

How to test it: Try offering three packages, and if there is something you really want to sell, make it the middle option.

Price perceptions

I’m sure you know the classic “pennies-a-day” effect: “it costs less than $1 a day!” NPR stations ask people to donate by joining their dollar-a-day club. Framed in that manner, the donation seems quite reasonable—about the cost of a cup of coffee. Contrast that with what would happen if they asked people to join their “$365 a year” club.

Neil Davidson writes this about price perceptions (in his book on software pricing called Don’t Just Roll the Dice:

People base their perceived values on reference points. If you’re selling a to-do list application, then people will look around and find another to-do list application. If they search the internet and discover that your competitors sell to-do list applications at $100, then this will set their perception of the right price for all to-do list applications.

If your product is more expensive than the common reference points, you need to change the perception of the category you’re in.

How did Starbucks get away with starting to charge $3 and more for coffee, when most other cafes were charging $1 or so? They changed the experience of buying coffee, so the perception of what people were getting changed. It was like a different category product.

They also changed the name. Not just coffee, but Pike’s Place brew or caramel macchiato.

If you’re creating a new category, there’s no price reference, and people are much more likely to accept any price you name.

How you can use it: If you want to charge more than the market average, look at the competition: how they package their offering, what’s the user experience like, and change that. If you look like a new category, people are more likely to pay up.

On the other hand, if you can profitably sell something much cheaper than the other guys, great. Use their pricing as the reference point and you’ll win.

Context sets perception

You are stranded on a beach on a sweltering day. Your friend offers to go for your favorite brand of beer, but asks: “What’s the most you’re ready to pay for the beer?”

This was the scenario for a pricing experiment conducted by Richard Thaler.

They tested two scenarios. In the first one, the friend was going to get beer from the only place nearby, a local run-down grocery store. In the second version, he was going to get beer from the bar of a fancy resort hotel. The ambiance of the hotel was irrelevant, as the beer was to be consumed on the beach.

Invariably, Thaler found, subjects agreed to pay more if they are told that the beer is being purchased from an exclusive hotel rather than from a rundown grocery.

It strikes them as unfair to pay the same. This violates the bedrock principle that one Budweiser is worth the same as another, and it suggests that people care as much about being treated fairly as they do about the actual value of what they’re paying for.

Thaler considered what his imaginary grocer could do to boost beer sales. He advised “investing in seemingly superfluous luxury or installing a bar.” This would raise expectations about what the proper price of beer would be, resulting in more purchases.

We happily pay $80 for 6 things in Whole Foods, but would consider that way too much in a regular supermarket.

How you can use it: Invest in seemingly superfluous luxury. Use web design or packaging that says “expensive.”

Can I split test the price?

Technically, you can, but A/B testing your price is a dangerous territory. A number of companies (Dell, Amazon, and others) have been caught in the past and got in trouble for doing just that, showing different price for the same product to different visitors.

A better and safer approach is to test the price across objects. Don’t test the same product for $19 versus $39. You should test two different products that essentially do the same thing, but just have a different price tag.

Before deciding on your pricing strategy, it’s worthwhile to read Cindy Alvarez’s article where she makes the point that price is not the only cost to consider. When customers consider “what something costs,” they’re actually measuring three main drivers: money (cost), time (how long will it take to learn?), and mental energy (how much do I have to think about this?). Take into account the profile of your buyer.

Combine research from this article

It seems to me that you could combine a lot of the research covered here into a single pricing experiment. How about this:

- You create three different plans/packages, and intend to sell mainly the middle one. If your product is expensive, make your website look expensive.

- The first plan is a decoy. It’s similar to the middle plan, but offers visibly less value while costing almost as much. Think of it as A- (as per The Economist example).

- Second plan, the one you want to sell, offers good value for money. The price ends with 9. Maybe it even shows that it has been reduced from a previously higher price or it’s a sale (either way, it has to be true/ethical).

- Third plan is to serve as a contrast to the middle one, its role is to anchor in a high figure. Make it much, much more expensive than the middle plan. You don’t actually intend to sell it, but there’s always the type that wants the most expensive plan—so make sure you can actually deliver on it.

If you decide to give this a try, let me know the results :)

Thanks for reading.

Working on something related to this? Post a comment in the CXL community!

“It opened it’s 4th restaurant of this kind in Portland…” should read “It opened its 4th restaurant of this kind in Portland…” (Or “…fourth restaurant…” if you’re following AP style.

P.F. Burns – Shut up, if all you came up after reading this article is a critique, you’re clearly have a high opinion of yourself douche. – Amazing article, gave me a ton of motivation and insight

Great post… but in the line, “The band allowed fans to download the album freely and offer, in retribution, any amount of money they would like.”, I *really* don’t think you meant “retribution” :-)

“Remuneration” would’ve been a better choice. P.F. Bruns: in the author’s defense, my iPad auto-correct always changed “its” (possessive) to “it’s” (contraction) until I modified the auto-correct settings!

Maybe reciprocity? :)

Great piece, always good to challenge the existing pricing strategy to try and maximize my result. Thoughtful suggestions, thx

Al

Very nicely summarized – thanks – I’d also suggest Robert Cialdini’s book “Influence” as a great primer and easy read on how to use subliminal and natural responses to sell and market products. (no – I’m not related – I picked it up when I heard that Warren Buffet gives away copies to everyone that comes into his office)

Really thought provoking with some great examples. Relating to my own personal expriences, each of these experiments proves true in my own pricing evaluations and thought process. I especially like the beer on the beach example (on multiple levels:-). The anchor in the real estate pricing example was interesting as well. Thanks for sharing.

Very nice. Perception plays such a huge role in pricing. People are always benchmarking and rationalizing the price off against some other expenditure. Unfortunately for me that is usually beer…which isn’t cheap :)

Thanks for sharing your experience. Already knew some and learnt about others. I loved the fact you used concrete examples to demonstrate your points

Great post. Regarding the final recommendation however: what can you do if you really have only one product without an easy way to ‘package’ it differently?

Package yourself differently. Or whatever they see between themselves and the purchase of the product.

Can you expand or cite an example of this Cliff? I am presently in the same boat as Yoav. I have a tablet bag company and we are in the midst of launching our first product. It’s our only product in the next 6 months.

Thanks ahead of time.

Depending on the product, you can add extra bonuses or support levels..

Support ticket, email, telep he support.

Upgrade to Done For You option.

What else could you value-add to price differentiate?

Great article. I really liked it. Thorough and complete. I’ll definitely be referencing this when people start to talk to me about pricing or ‘testing’ their pricing. I’m also going to follow you now :)

That was very informative. Way to go!

Pricing is something I’m working through right now. This was great.

Thanks for the piece. very well researched. I’ll be using it as a reference!

I wonder if when you suggested we could download a PDF that you had included a ‘pay what you like’ field, you would have made some $$? After the good feeling of reading this great piece I would have stuck at least a dollar on it. All the good Radiohead fans did, and you clearly spent time researching this and working hard to inform your readers. (Just my $0.02) ;)

Thanks Peep, useful research.

I always ponder in amazement how people are willing to pay $50 and upwards for an eBook but balk at paying $20 for a physical book.

So much psychology!

Cheers

Thanks much for such valuable information, i would add (maybe to the number 4) following also the contrast principle that your expensive package should be first on the list.(of the three)

best and thanks again!

I don’t believe i read this whole article in english (i’m french), but it was very interesting and make me think about my real estate business. I would be happy to traduce it on my blog “500k”, so if you would be happy to be traduce on a french blog, make me known it. bye and i bookmark your site & tweet this.

Great value article. The stand outs for me were “Can I split test the price?” and “They changed the experience of buying coffee, so the perception of what people were getting, changed.” it is all in the way of how you package it.

Great article. We’ve done a lot of price testing. One comment: Dan Ariely’s “Economist” experiment is bogus. We tried that – on real people vs. his hypothetical – and found the decoy price makes no difference. Even the Economist doesn’t price that way any more.

Great reading! This will be very useful in my everyday work

Thank you!

Wonderfully written! Wow. So helpful and easily applicable. I really appreciate this. Thank you!

This was well thought out and very very useful. Thank you!

So much gold in here. Thank you! Going to test some price strategies to increase my conversions.

Great insights from this article. I do freelance videography and notice more and more how the packaging of my service extends to so many elements other than just my video (i.e. my business card, having a business email address, my website, my email signature, the way my invoice is laid out…etc) to create a cohesive impression that makes the price that I ask for seem fair. Thanks for addressing this gray/uncomfortable topic that is essential to my livelihood. Cheers -George

Ah this is fantastic! I think the idea of a simple 1-price option resonates with me the most, but we do present more expensive alternatives first. We also do our best to legitimately offer far greater value than the price, which is an option with digital products.

Is 9 still the go-to number? I’ve heard that it’s 7 now, and soon to be 6.

Some great tips, I’ve been struggling finding my right price points. I think I’m going to focus on the anchoring, your tip to offer a high price on ballpark estimates was gold!

Great Article! One pricing strategy I tried on craigslist that worked is using the perception of higher quality based on price. I attempted to sell a used queen mattress I bought originally (brand new) for $120. I did not use the mattress much, in fact it was still in its wraps when I decided to sell it. The original price I set, which I thought was reasonable was $80. I got very few leads, and was unable to close any of the leads. Then I changed the price to $200 just to test the perception of higher quality based on price. I got 5x more leads (mostly women for some odd reason) and was able to close for a profit! As discussed, the perception of higher quality based on price actually works. It seems irrational and unethical; however, it works.

Great article. Thanks for all the research material. We humans are really funny.

Hello Peep,

Thanks for your great article with so many cool researches.

I have found few new cool ideas as well.

Regards,

Igor

Nice article with a case study to experiment with. Thanks a lot, it worth it.

This is a great summary. I’ll keep it on hand for future reference.

The only thing I didn’t see mentioned is the “paradox of choice” factor, whereby the more choices you give a buyer the less likely they are to choose any at all.

Thanks Wayne. I’ve covered paradox of choice is several other blog posts, but not here as it’s not directly a pricing issue.

What a brilliant article! I also noticed the story came to an end just right when I was about to get bored!

Great post. I am going to re-consider my price scheme.

Thanks for the research you put into this! Pricing has been one of those things that has always been mind-boggling for my business. Now I can actually put some science behind my price structure and stop hoping that this $xx.xx works!

This is the best pricing article I have come across. Thank you!

Fantastic article! Always struggling to figure our best price for product. Definitely going to test a few of these examples. Thanks!!

BLew my mind away! Definitely own of the best pricing article so far.

Does anyone here has any experience in using service like visualwebsiteoptimizer.com to A/B split test their pricing?

This was a great article, good insight, and interesting things to think about for perceived value, price anchoring, and the mysticism of the number 9…

Love Predictably Irrational! Great book and a must-read. I always like the wine menu technique of anchoring with a high-priced item even if people won’t buy it.

I didnt read all comments but the origin of .99 and .95 price endings was when the merchant wanted to force cashiers to give change instead of slipping the note into their pocket. (General rule of retail is staff are not allowed to carry money on them so cant give change out of their pocket).

Customers will spend $100 and wait for the 5c change. We are funny that way…

Great article

Is there a primary source to a single peer-reviewed scientific journal article anywhere in here? Seems like just a bunch of hypotheses and self-published pseudo-science so far.

Chris Dean: most of the experiments in here are indeed based on peer-reviewed papers, but I agree it is best not to take them purely on trust. I looked them all up for the bibliography of my own book (not listed above, but then it did come out after this blog post), The Psychology of Price: http://amzn.to/leighbook

On counter-clock-wise average basket-size increase:

I am willing to bet this has something to do with more people being right handed than left handed. It is easier to reach with your dominant hand and when you are moving counterclockwise the outside of the supermarket is to your right and there are more products along the wall (to your right) than there are on end-caps and shelves to the left.

Strong article with a ton of pricing intelligence. I think 7 might have replaced 9. At least online. I see 97, 37, and 147 all over the place for product offerings online. Looking for data on this angle.

Glad I came across this. Im coming up with the prices for my services and feel a bit comfy following what the big companies are doing. I always noticed that most stores don’t have numbers like 25. It’ll be 24.99 or 24.97.

Great read. Thanks for sharing

Brilliant! Thanks so much for all of this critical analysis.

What are your thoughts on $97 vs $99? And what makes a “website look expensive”?

Thank you!

This has to be one of the best articles I have read on pricing! Absolutely brilliant. Will implement few of these strategies on our product that we are going to sell next week!!!

Thanks for such an awesome article. Really interesting aspects of pricing strategy. When an article force you to think more on the subject then I categorize that as Masterpiece!! This is one of those articles.

Very good info. Lucky me I found your website by accident (stumbleupon).

I’ve book marked it for later!

This was a great read. I have had the problem of not knowing what to charge and I end up giving myself away for way to cheap. After reading this I am going to try some of these technics.

For an extended time, checking your {internet site|website|web-site|web internet site|web-site|net site} having a rising curiosity. Jots down really interesting, the subject areas that

In July of this year I ran an A/B/C experiment on a popular ecommerce website to test the anchoring effect, and the results were astonishing. An 11% increase Average Spend per transaction in direct sales, and a 26% increase for indirect sales. You can read the full write up at http://econsultancy.com/uk/blog/63250-mind-games-using-heuristic-theory-to-increase-customer-spend-online

Did you write this article also?

http://econsultancy.com/us/blog/62591-why-pricing-experiments-prove-our-assumptions-are-wrong

This post has really made me to comment on it, the sheer value it gives, Peep Laja wish I knew you from the first day I started my own business!! great man! hats off!!!

Something I experienced in the 3 model scenario is naming the product. Some may find this very interesting. I had a $3000 Model, a $2400 model and a $1800 model and all had the same benefits basically but as price increased the value did as well, so what I did was play with the name of each model…My middle model sold the best by far ($2400) Then I came up with an idea based on learning my customers and realizing they took great pride in being called “Professionals” so I thought I would test my product names based on this. I deal with contractors in the home/business building sector and changed my model names from #1, #2 and #3 to The “Professional Series” ($3000) The “Contractors Series” ($2400) and then the “Homeowners Series” ($1800) We never sold/sell one unit to a homeowner…..we went from our middle option being the best seller by 2x, to the top expensive model being the new top seller….it didnt double but its close and a very big reward! people like to have an ego when they make a purchase and want to be thought of as an elite of some sort. Our sales guys ask from time to time…are you a homeowner? Are you a Professional contractor? This was an amazing breakthrough for us. We are currently launching a new product and get the benefits of launching with this tip.

Great article and summary Peep, thanks!

You might like to add this bit to it…

The Rule of 100 says that under 100 percentage discounts seem larger than absolute ones. But over 100, things reverse. Over 100, absolute discounts seem larger than percentage ones.

Ref: http://jonahberger.com/fuzzy-math-what-makes-something-seem-like-a-good-deal/#more-1942

Sharing is caring :)

That just reminds me of Kickstarter reward options.

Great Piece . very informative. consistent smart update to pricing strategy pays.

I love this post, this is what i am trying to do and figure out with my social media services. Well pricing is very tricky becz you need to get the best price. I have offered my SEO services between $50 and $100 as low cost one time package, that’s cool na :) But its all about how to sell the best services by attracting customers just as i do!

I have learned the hard way to get the right pricing in my business, your article is very informative and help me a lot, thanks.

I liked this article, in fact i was practising it, but it gave me more motivation.

But here one thing is missing for markets like ours, where we are dependant on retailers for our sale and we don’t have budget to advertise, we do same practice for them but still we don’t get desire results. what other techniques we should use so the retailers(who assume that they know 100%) compel to give us cent percent results.

Great article. I really love it. this information is useful so we can have a second and third option. Congrats!

Do you know a good tool to do a/b testing of prices? Because doesn’t it have to communicate with the backend? It sounds complicated but if there is a tool to make it easy I am up for testing it!

Wow! Thanks for the articles. Great readup and information!

Freaking brilliant article! Thank you!

Just so you know, that your article has been copied:

http://www.blueperks.com.sg/5-pricing-tactics-you-always-fall-for/

Great article. The three options tip is very true. If you offer a three package solution…a percentage of people will always go with the premium package.

You’re losing money if you’re not offering premium packages in your business. Great article Peep.

Really interesting article!

The beach-beer example reminds me of something I’ve often noticed about myself when considering prices. I used to go garage saling a lot and made a habit of bargaining down prices. Garage sale prices are much, much lower than any other kind of shopping I’ve done–a shirt that would cost $15 in a store would be worth maybe $2 max at a sale. (Most of the time, the sellers just want the junk out of their house and don’t care much about profit as long as they’re getting SOMETHING.) Yes, most garage sale items are used, but sometimes people sell new-in-box or as-good-as-new items. My price standards are way different. An item that I’d be willing to pay $30 at a store being sold for $5 at a garage sale seems super expensive to me–I’d bargain it down or pass it up unless I needed it urgently.

The three-beer example makes me think of something else I’ve read–it was years ago so I’m afraid I have no clue on the source. It goes like this: A jam seller on the side of the road offers one flavour of jam and makes good profits. A similar jam seller who offers a lot of flavours makes less money. Why? Because for one flavour, the customer has only one choice to make: Buy or don’t buy. For many flavours, the customer has two choices: Buy or don’t buy; buy flavour a, flavour b, etc., or don’t buy (because none of the flavours look good). That gives the customer two chances to choose “don’t buy.” So it’s funny to see a similar example being used with the opposite message.